12.11.2021

Crucial to understand how CO₂ moves in a reservoir

Researchers at the Institute for Energy Technology (IFE) have been studying how sequestered carbon dioxide moves through so-called chimneys in rocks, providing new knowledge about how CO2 can be safely stored in geological formations.

Stored safely for years

Carbon dioxide has been stored safely in the Utsira Formation in the North Sea for years. The formation contains a number of vertical structures called chimneys that allow CO2 to flow between the different sedimentary layers. Chimneys have also been observed in the sealing layer of the cap-rock above the Utsira aquifer. Utsira is a safe site for storage of CO2, but in order to find new, safe storage locations, it is important to understand how these chimney structures are formed and behave.

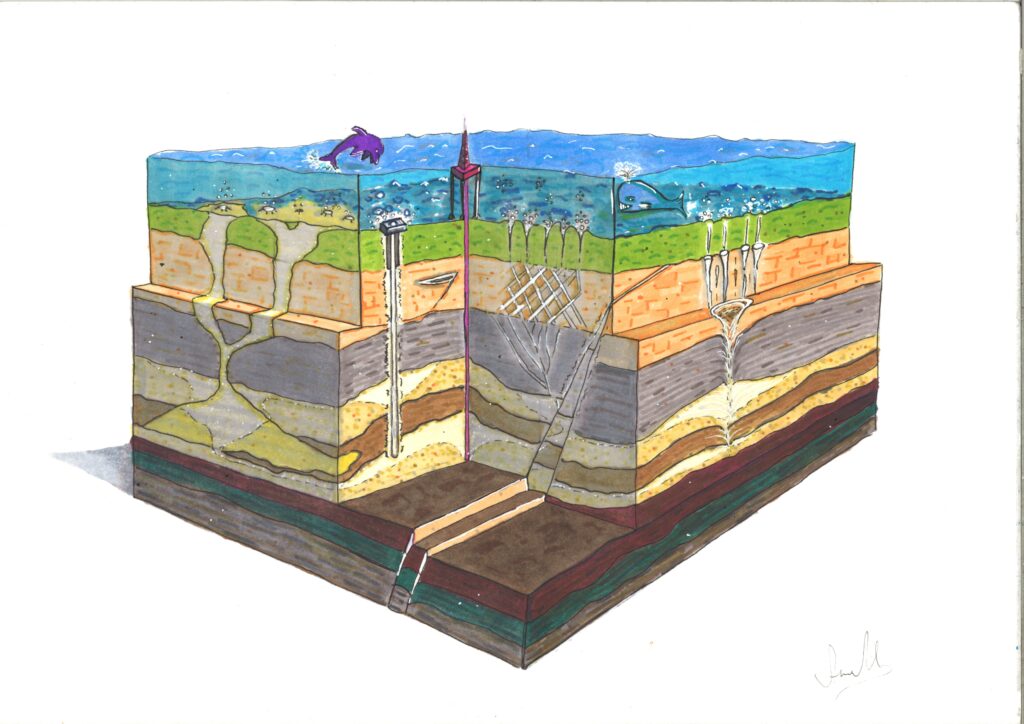

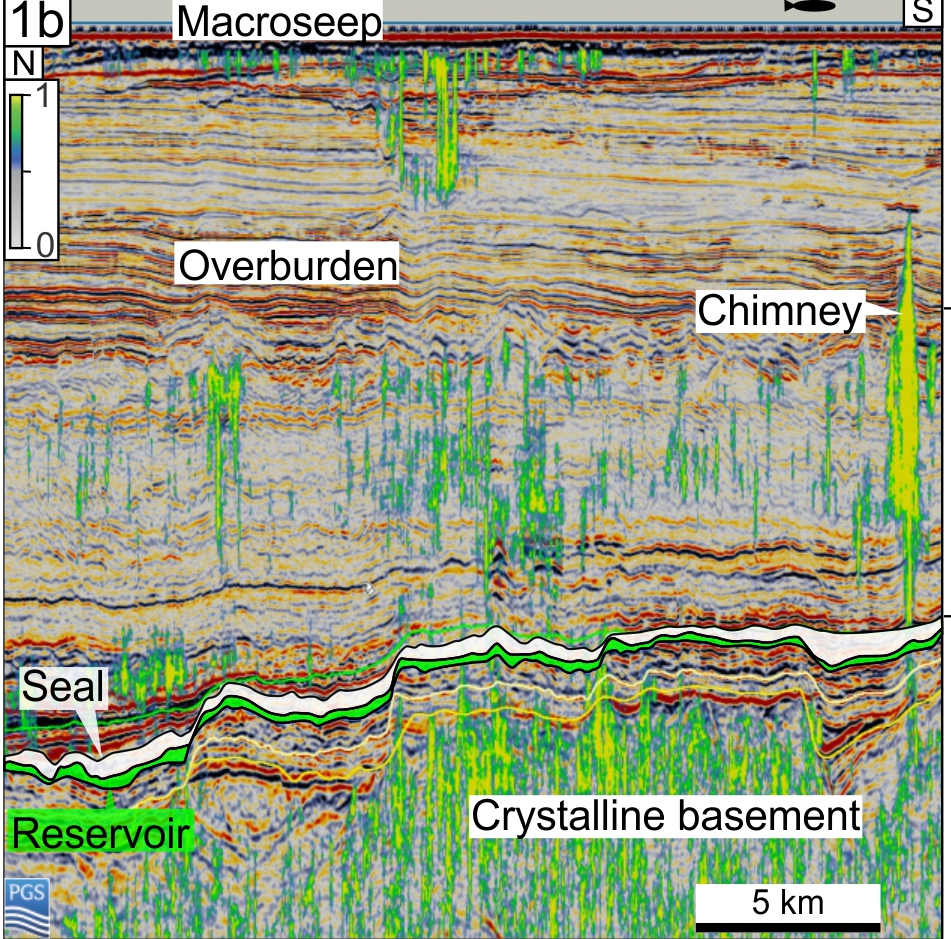

Chimneys are explained in the figure below. The rock deep below the seabed is made up of many horizontal sedimentary layers. Chimneys are vertical channels that connect the various sedimentary layers. Liquids can, in principle, move through the chimneys and thus move from one layer to another.

All CO2 remains in place

Although chimneys have been observed in the sealing cap-rock layer above the Utsira aquifer, there is nothing that indicates that CO2 is moving out of the storage site. All the CO2 that has been injected into the Utsira Formation stays where it should be.

The figure below shows that chimney structures are common in close to impermeable sedimentary layers.

Important to understand the structure of chimneys

The Utsira CO2 reservoir is tight, but in connection with developing new sequestration sites, it is important to fully understand chimneys so that we can be sure that new storage sites also remain tight.

In the CO2-PATHS project, researchers from the Institute for Energy Technology (IFE) and the Norwegian Institute for Water Research (NIVA) have studied these chimney structures in detail. The researchers have created physical models to determine how chimneys are formed and how they behave. Project manager Magnus Wangen says this has generated important new knowledge.

“We have concluded that chimneys have such low permeability that they will cause negligible CO2 flow from a reservoir. However, to ensure safe storage, it is necessary to monitor chimneys located above or near CO2 reservoirs,” Wangen points out.

New understanding

The chimneys that are visible today were formed way back in geological time by high fluid pressure. Reservoir fluids can move in the chimneys, and the lightest components will move upwards. In the project, the researchers studied how glacial processes created high pore pressure in sedimentary layers in the Utsira aquifer. This has provided new understanding of how fluids move in chimneys. The project has had a particular focus on whether chimneys can form in the cap-rock that prevents CO2 from flowing out into the sea. The researchers have built models for pressure build-up caused by glacial loading and have studied how viscous deformations can form chimneys in sedimentary basins.

CO2-PATHS’ new physical models will be useful for researchers and operators of CO2 storage sites.

“The knowledge generated in CO2-PATHS will be very useful when assessing new storage sites. We now know more about chimneys, and this has increased our understanding of how CO2 might move in new storage sites,” says Wangen.

The results of the project have been published in a series of scientific articles in internationally recognised journals.

Key data about the project

- Title: CO2-PATHS – Prediction of CO2 leakage from reservoirs during large scale storage

- Project number: 280567

- Partners: The Institute for Energy Technology (IFE) (project owner) and the Norwegian Institute for Water Research (NIVA)

- Project period: 2018–2021

- Budget: NOK 8.2 million. Funded in its entirety by the Research Council of Norway